Poetry Review

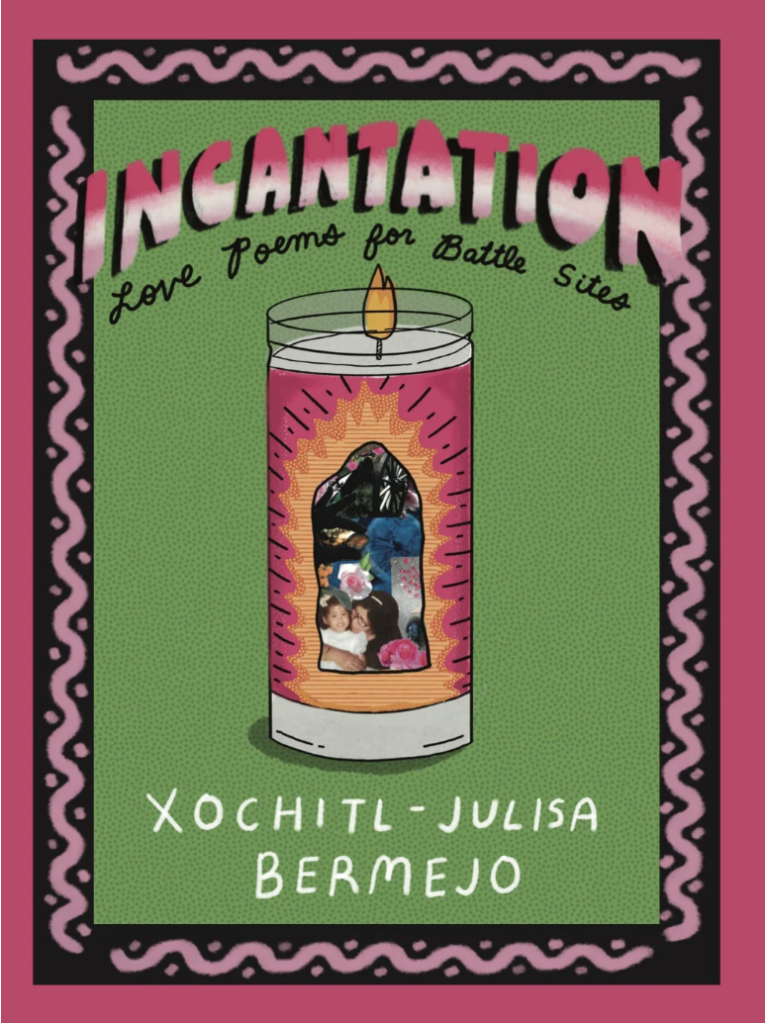

Incantation: Love Poems for Battle Sites

by Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo

March 3, 2025

In Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo’s poem, “For the Love of Home,” she writes:

“Fire is renewal. Land

cannot forget. Land

is mother. Mother’s womb

is structure. Ash

is not nothing. Futures

are sketched in ash.”

This memory of place and its inhabitants guide Bermejo in her book, Incantation: Love Poems for Battle Sites. Her three-part collection contains harrowing acknowledgements and loving reimaginings of unjustly harmed, removed, and massacred peoples—while offering tender, sometimes lustful, explorations of determining her place as a daughter and lover. From the U.S.-Mexico border to the Gettysburg National Military Park, Bermejo is keenly aware of how it feels to exist among repeated cycles of violence—“Consider rising. Consider reading. Consider walking. Consider the helicopters, still circling”—yet believes to name a fear is resilience: “Our screams are the fertile soil holding the bones of every woman’s scream / that came before us. Our breath and saliva feed the hills we raise together. The hills our nieces and / daughters climb to paint birds, be an ocean.” Readers of these poems are beckoned to join Bermejo’s incantation to revive to our consciousness the lives of children crossing borders, of working-class Angelenos, of Black and brown bodies murdered by state-sanctioned violence, of her own lineage, and the labor necessary to survive.

How do you memorialize a child while holding onto their joy? Part One considers that question, as Bermejo dedicates poems like “Ursa Minor,” “Mamita, We’re Going On Ahead,” and “Beach Evening Primrose” to children and the young with preventable deaths, especially those crossing into the U.S. Many of her poems contain dedications with reimagined images of the natural world embracing their lives, such as that of Claudia Patricia Gomez González, a Guatemalan woman shot by a border patrol agent in 2018: “One day, we’ll be reunited, but my blood stays, / soaks the soil, stains their precious border.” Rivers, insects, flowers, mountains—these motifs truly are Bermejo’s landscape, paralleled by descriptions of indoor and outdoor labor within cities like Los Angeles. It is within her prose we find return to home, resistance, and commemoration.

Still, the memories of poems’ subjects do not feel like hauntings. They feel beckoned, deserving to be heard. Perhaps influenced by her time at the Gettysburg National Military Park, in “Ghost Interview with a Soldier in the Peach Orchard,” she momentarily pulls away from the external of the battlefield to ask, “In your final moments, whom did you think of? / Did you write this someone love letters home / with sign-offs like I wait to hold you and Forever yours?” She is concerned with the love exuded by an undefined soldier of the Civil War, determined for a moment to acknowledge their spirit despite their decision to participate.

Though much of Part Two is a reflection of inconsistencies and irony of the park’s telling of history, Bermejo closes her collection with complete, undeniable passion. Part Three is full of poems of self-love, pleasure, and eroticism. She calls back to borders in “Rancherita” through her body that cannot be contained, and in “I’m Not Your Torta,” a vulva shaped poem addresses a “you” that cannot “even think of bearing your / mouth to this deliciousness.” She parallels lovers and partners with misogynistic values, understanding the risk of removing oneself for the sake of others, “And when they call me / “muse,” I know they mean comfort.” Bermejo is an artist who admits her feelings of loneliness and fear, wanting to believe there is a love for her; yet, in the push and pull of wondering what is deemed acceptable pleasure in a woman, her grandmother said it best, “’¿Porqué no comes? ¿No tienes / hambre?’ As if to say, want / could never be shameful.”

Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo was published in Huizache 8 and 9.

– Marilyn Ramirez, Huizache Staff