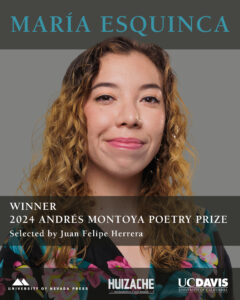

An Interview with María Esquinca

Winner of the 2024 Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize

Born in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico, María Esquinca grew up in El Paso, Texas. She now lives in Oakland, CA where she is a producer for The Bay podcast, a production of KQED. She was previously a New York Women’s Foundation IGNITE Fellow with Latino USA and a 2020 Report for America Corps Member at Radio Bilingüe. María graduated from the University of Texas at El Paso and received her MFA from the University of Miami. Her poetry has appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review, Waxwing, The Florida Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Cream City Review, and others. In 2018, she won the Alfred Boas Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets judged by Victoria Chang, and in 2024 she won the South Carolina Review Ronald Moran Prize in Poetry. Former US Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera selected her as the winner of the 2024 Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize.

Jessi Jarrin, a UC Davis MFA Creative Writing student, conducted the interview with María via email in the weeks leading up to the prize announcement on May 18, 2024.

How does it feel to win the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize?

I don’t think I’ve fully processed my feelings. I’m still in shock. This has been a dream of mine for a long time. If I really think about it, I’ve dreamt of having a book published since I was a teenager. I started applying to book contests after graduating from the University of Miami’s MFA program in 2020, so I’ve been sending this manuscript out for four years. When I read the email notifying me that I won, I started screaming for my roommate. I didn’t even finish reading the email. I told my roommate, Quinn, that my book was getting published. I just kept stuttering, “I can’t believe it, I can’t believe it, my book is getting published.” I was in a state of shock. I couldn’t really process anything other than the shock of that news moving through my body. And I still kind of feel that way. Dismay, shock, and big joy. It’s a very surreal experience when you finally get something you’ve imagined for so long. It felt both long and sudden. I still can’t fully wrap my mind around it. Part of the surrealness was that I started the year saying, “This is the year I’m getting my manuscript published.” I spoke it into existence and then it happened. Now we’re here.

What was your introduction to poetry?

I think most people, when they speak or think of poetry, they think of the written page or the spoken word. I think of poetry as not just an act of writing or orating. I recently watched a video of Lucille Clifton where she says poetry is a way of existing in the world. It’s a way of being, seeing, absorbing. Lucille Clifton also talks about being ready for when the poem arrives, so in a way, it’s a bodily act too. It’s corporeal. It’s something that exists beyond the page. So, if I take Clifton’s definition, my first introduction to poetry must’ve been the moment I was born, removed from the warmth of my mother’s womb, in which I imagine the sounds of the world violently poured into my ears and I screamed back.

If I take the more traditional understanding of poetry, it must’ve been in elementary school. I remember we had an assignment in my fourth-grade class where we had to write a poem and my poem won a class contest. But when I really discovered poetry, which is to say, when I fell in love with poetry and felt it enter my heart and move my soul was when I took a creative writing class with the poet Sasha Pimentel during my undergrad at the University of Texas at El Paso. We read Patricia Smith, Philip Levine, Federico García Lorca, and Dorianne Laux, among others. That’s when I realized how special and unique poetry was. My discovery also had to do with how good a professor Sasha was. Every day, I would leave that class completely moved. She was one of those teachers that leaves an impression on you that lasts a lifetime and completely alters your life. My discovery of poetry has always been facilitated by phenomenal teachers.

You were born in Ciudad Juárez and grew up in El Paso. As a fronteriza, how does the border inform your poetry?

It informs every part of my being, so by extension it influences every part of my poetry. As fronterizxs, we grow up in a liminal space, what Gloria Anzaldúa calls a “third country.” It doesn’t feel like we’re fully in the states, or fully in Mexico. Every time folks that aren’t from El Paso visit, they’re surprised by how close Mexico is to us, that you can see Ciudad Juárez from the I-10. You can cross a bridge and in a few minutes, you’re in Mexico. El Pasoans often have family in Juárez and vice versa. People cross all the time between the sister cities to shop, to work, to go to school, to club. It’s always fascinating to me that people who aren’t from the border speak of division when actually it’s a community that has always been connected to each other. The wall has never really separated us, there’s always a relationship there (that isn’t to say that some folks can’t cross because of their immigration status.)

That sort of liminality has influenced my way of moving through and understanding the world. As a fronteriza, I learned very early on that borders or limits are inorganic, and artificially placed on people. That freedom enters my poetry. To me poetry is the purest form of expression precisely because it has no boundaries. It has no limits or walls.

I know there are rules and conventions that get taught and which are imposed on poets. The “you shouldn’t do this” or “you shouldn’t do that.” I don’t believe in that. To me, poetry is the antithesis of that. It’s one of the few spaces in my creative practice where I can really do anything. It’s where I can make weird things with text like with some of my visual poems, or I can imagine a world that doesn’t exist by using surrealism, I can impose non-realistic elements like with magical realism and make my mom become a toad or a mermaid that jumps into the ocean. It’s the most freeing thing.

Beyond that, content-wise, a lot of poems in this collection are about El Paso and Juárez, about growing up there, about my family and friends, but also about the way in which immigration policies that are created by mostly white people with no relation to, or understanding of immigration, affect us and our refugee brothers and sisters. At the time I was writing this manuscript, Donald Trump had just ascended into power and I was in Miami reading about the horrific things his administration was doing to immigrants. I was seeing children separated from their families. I was seeing immigrants kept outside in tents like animals under numbing heat. I was witnessing Steph Miller and Jeff Sessions create some of the most horrific immigration policies I had seen in my lifetime. I was angry, scared, saddened, desperate, and my heart compelled me to write about the border and immigration.

I started delving more into documentary poetics and in my research discovered that Silvestre Reyes, an El Pasoan, the son of Mexican immigrants, son of farmworkers, was the mastermind behind the border wall. Back when he was a border patrol chief, he ordered Border Patrol agents to stand across the border, he created a wall of humans, to block people from crossing into El Paso. This later was adopted under Bill Clinton in the 1990s and became the blueprint for “Prevention Through Deterrence,” the de facto US immigration policy which has led to thousands of immigrant deaths by forcing them to immigrate through some of the most brutal parts of the Sonoran Desert. And it was all started by an El Pasoan. And then I was really pissed and had to write about that too. This is all to say that, again, being a fronteriza informs every part of my poetry.

How does being a journalist inform your poetry? How does it shape the craft or the content?

I long felt that journalism was a life calling because it was a way to tell people’s stories and to hold people in power accountable. I felt I could mix my passion for writing with social justice. I’m not so sure of that now, but I think most people get into journalism because they believe it’s a way to make a difference in the world. When it comes to the political parts of my poetry, that’s absolutely informed by journalism. My pointing to injustice, violence, state actors, elected officials, folks that are being abused or oppressed, that all has its root in my journalism background.

My decision to include quotes from newspapers I found, like “Era Solo un Niño,” a pantoum poem about Sergio Adrián Hernández, barely a teenager who was shot over the fence by border patrol agents for throwing a rock at them, is informed by my journalism. The title of that poem is taken from a quote from one of his family members I found in a Mexican newspaper, Reforma. There’s also a quote from Silvestre Reyes, who at the time, in defense of the border patrol agents, said, “Let’s not forget we’ve had border patrol agents killed on the border as well.” That was taken from an article from the El Paso Times. The skills I learned as a journalist to interview, research, and source were all drawn from my experience reporting.

On the flip side, I’ve had a lot of inner reckonings with journalism that have led me to love and appreciate poetry in a way I might not have if I hadn’t been a journalist first. There’s a lot of restrictions and limitations within journalism, both at a content level and politically. As someone who is both creative and opinionated, I’ve felt very restricted. So, to me poetry is where I can do anything, be my full self, and say whatever I want. I also have a fascination with headlines, and I’m obsessed with language. I think a lot about words and their power. Part of my disillusionment and frustration with journalism, especially in a time like now, is how inaccurate it can be in its description of events, particularly when it comes to marginalized folks. We’re witnessing headlines that diminish the atrocities being committed by Israel against Palestinians, a pattern or behavior that was very apparent during the Trump administration too. We see words that don’t accurately describe what is happening, diminish and minimize harm, obfuscate, or remove the actor who is committing violence through the passive voice.

I’ve felt that poetry in many ways allows me to be more honest and accurate than journalism. However, one thing I’ve always appreciated and returned to is that journalism was created with the intention of being a check on the government, it has democratic roots, and because one of its purposes is to inform the public, it’s written in a way that is meant to be accessible, concise, and clear. That has influenced my poetry too. There’s poetry that I know most people in my life outside of poetry circles can’t access. There’s a value in being able to make your message accessible, whatever it is. As a producer, I also have to edit all the time. It’s my job to cut down an interview from forty minutes to twenty minutes, so that too has really sharpened my ear. It’s really made me able to identify what is necessary, from what is extraneous. I’ve applied those skills in my poetry, and it has made me a better editor of my own work. Beyond that, my journalism background made it natural for me to engage with documentary poetics, which has crossover with journalistic practices, like the use of first sources, interviews, evidence, etc. I’ve applied those elements in my poetry about the border and Donald Trump’s immigration policies.

Who have been some of your most important influences?

Looking back, I was very lucky that I landed in the University of Miami, the only school that accepted me because I got to study under Maureen Seaton, who sadly passed away last year. I didn’t know it then but having Maureen as my teacher and thesis advisor was one of the greatest gifts the universe could give to me. Maureen was one of those people who loved you as you were, who could see you and accept you, and not try to change you. As I get older, I’m realizing that’s a very rare quality, it is a form of pure love. That love extended into her teaching. I didn’t know then that I was doing some funky things. I was just writing. I think if I were in another program that was more traditional, under folks that emphasize norms and conventions, it would’ve been disastrous for my writing. Because then I was younger and more susceptible to care about that type of advice. But Maureen herself was a writer whose poetry changed and morphed through the years. I think she embodied the sort of freedom and liminality I mean when I talked about growing up as fronteriza. She herself was never one thing and didn’t impose that on any of us. Maureen saw me and allowed me to be the poet I am. She encouraged me and allowed me and my writing to blossom. I think in many ways she saw me before I saw myself. Aside from that, at the time I was in a very dark place navigating an emotionally abusive relationship. Maureen was an angel, if it wasn’t for her, I don’t think I would’ve finished the manuscript or the MFA. I would say she was and continues to be one of my greatest influences. She not only taught me to be a better poet but a better person. She teaches me how to move in light.

Sasha Pimentel is the reason I pursued an MFA. I didn’t even know what an MFA was until she talked to us about it in her class. Her devotion and discipline towards poetry continues to reroute me. Her attention to craft and language marked me early on. I’m influenced by my friends who are fearless writers like JJ Peña and Saúl Hernandez. I’m also influenced by writers who surprise me, who do things that are unexpected like Carmen Maria Machado, Tommy Pico, Maggie Nelson, Claudia Rankine, M. NourbeSe Philip, Larry Mitchell, Ilya Kaminsky, Elena Poniatowska, Phillip B. Williams, Mónica Ojeda, Mariana Enríquez, among many, many, more. I also have to name my Latinx influences who’ve shaped and laid out a path for me to follow like Juan Felipe Herrera, who I’m beyond honored to have chosen this collection, and Andrés Montoya, who’s the reason my book will be out in the world, but also Gloria Anzaldúa, Cherríe Moraga, Natalie Diaz, Eduardo Corral, Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, Gris Muñoz, and of course the Juárez poet and activist Susana Chávez Castillo. I’m missing many folks here but those are just a few.