An Interview with Fernando A. Flores

December 16, 2024

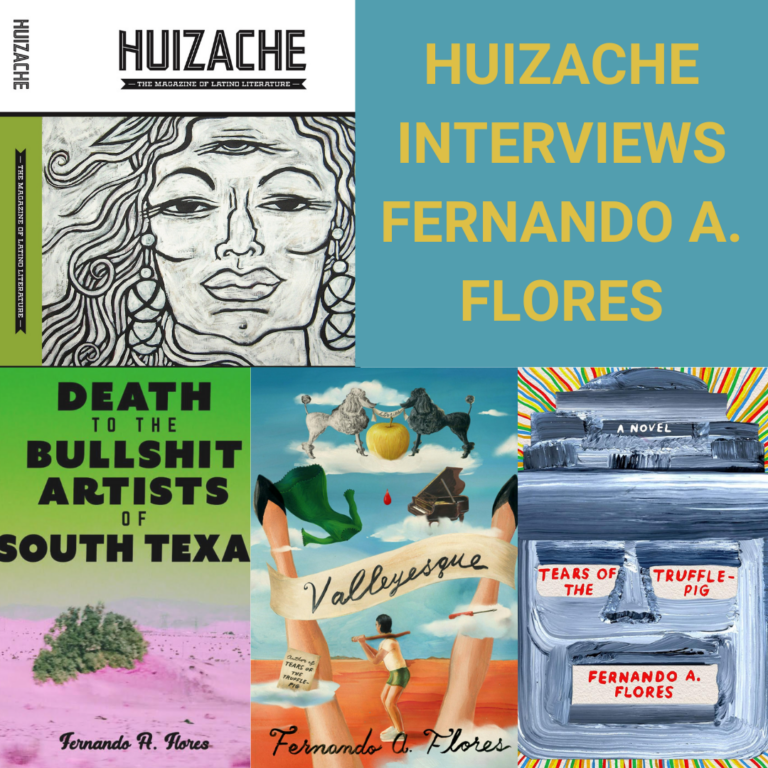

Fernando A. Flores was born in Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico, and lives in central Texas. His short story, “The Eight Incarnations of Pascal’s Fifth,” was published in Huizache 5 in 2015. He is the author of Death to the Bullshit Artists of South Texas, Tears of the Truffle-Pig, Valleyesque, and a new novel, Brother Brontë, coming out February 2025. I interviewed him about his book of short stories, Valleyesque, published in 2022.

I first got my hands on Valleyesque at the library. Which is great, except this isn’t the kind of book you’ll want to give back. It stays with you as you walk down the street, as you go to work, as you interact with your family, friends, and neighbors. What was up with that angel again? How much money did those kids get for that Grackle they sold to the old man? If I ran into you at a bookstore holding the book, I might feel the urge to follow you around. That’s why I was so excited to get the chance to ask Fernando Flores a few questions about this curious and engaging collection of short stories.

– Brennan Havens, Huizache Staff

This interview was lightly edited for length and clarity.

I love your book Valleyesque. I also write about a valley, California’s Central Valley, where I was born, raised, work, and am now still. In your story “Nostradamus Baby,” the narrator talks about his writing, stating, “I feel I can reveal more by writing stories in the tradition of hard-core, maybe weird literature, rooted in something old and unknown, and infusing it with my life and where I come from, as unintentionally as possible.” This seems to be the key to your own work. How do you define hard-core, weird literature and what has been its influence on your development as a writer? What about the Rio Grande Valley makes such a key intervention in this tradition?

Funny, this passage is often mentioned when people ask about my work. It was definitely unintentional, but it’s interesting to me how bits like this can sneak into our work if we have our minds open. I’m not sure I have a definition for “hardcore, weird literature.” I am the type of person who never said: I want to be a writer. It just sort of happened. For years and years nobody knew I was a writer, unless you were a friend or roommate who saw how I lived. My family didn’t even know. I dropped out of college and had no writer friends for most of my life.

The literature and type of writers who have emerged from the Rio Grande Valley also tend to be almost exclusively realist, and strictly follow that tradition. As an immigrant, and feeling always like something of an outcast, even from the Mexican American artistic community, I never felt I needed to be loyal to any kind of tradition, literary or otherwise. My goal was always to write a story I could be happy with. That’s it.

Many of your characters reject technology. In the story “Queso,” Marcos throws a glass at his TV. In “A Portrait of Simón Bolívar Buckner,” Gabriel puts his TV and computer on the curb. In “You Got It, Take it Away,” the narrator is annoyed that the jukebox in a bar was replaced by a digital one. These characters seem to reject the intrusion that technology has had on their lives. I’ve heard that you write on a typewriter. Do you feel that technology is something we should be questioning or outright rejecting?

I never write with an agenda in mind, so I have to conclude that these patterns that emerge in my work happen because that’s how I live my life—I try to reject technology as much as I can, mostly out of convenience, and to try to protect my long-term attention span, my cherished solitude, my creative brain. Writing on a typewriter simplifies the writing process: it’s just you and the page. No glowing screen, no blinking cursor, no Microsoft. You can see your mistakes, your failures, directly on the page, which is invaluable.

Working on a typewriter is also a subconscious reminder that I am a worker and have the same concerns as working people. With moments of respite since my first novel and the movie options were sold, I’ve mostly lived paycheck to paycheck my entire adult life and struggled with rising rent and cost of living—to this day. I don’t have a degree and don’t teach for a living; also, years of working in the food service industry have rendered me borderline anarchic when it comes to working in any institution and possibly completely unemployable in the long-term. A person such as myself is almost unrepresented in contemporary letters. Coming home after a shift at the bookstore, having the rent paid, getting some words down on the typewriter—that’s what keeps me plugged in.

You’ve mentioned in other interviews that you don’t intentionally make stories political, but your story “The Science Fair Protest” seems, at first, highly political. There’s the erasure of science, the control of resources by those in power, the narrator’s political apathy. But then you also introduce this idea of literary landscapes—a scene from Proust—infiltrating the narrator’s reality. What is the power of art in determining our lives that the political fails to understand? I want to believe that art matters, but I also fear that that’s bullshit, that’s it’s just an excuse to disengage. I guess I want to hear what you think.

Is creating art an act of disengaging? I’m not sure. At least for me, it isn’t. I don’t approach writing stories with an agenda, and that includes politically, but this is only so I won’t be closed off to writing about things I wouldn’t normally conceive of. All these things you mention about “The Science Fair Protest” came together because I was open to them, and as a writer it’s my job to make it all work.

Often, a theme, or a scene, comes to me while writing a story, and I have to stop writing after its appearance. To soak it in, try to understand it, and try to see how I can move forward with the story. I rarely take something out of a story once it’s written—I write my way out by moving forward with it, rather than to edit it out. I feel I learn more about my characters this way, too.

Our world is constantly so charged politically that to avoid any of it seems like a willful act—one that I would distrust from any writer. My job is to grapple with it all, and, most importantly, to write a story that I feel only I can write.

Can you tell us about the angel in the story “Pheasants,” who loiters in the alley behind where Tito Papel works, eats trash and throws up rainbow oils? How did that character come to you?

Like with all the stories in Valleyesque, this one was written when I could find the time while working either as a barista or a bookseller. When you work in the restaurant industry during apocalyptically busy shifts, there’s often about a minute of silence in that moment you step outside to throw away a stuffed trash bag into the garbage. There’s something sort of incongruous about this moment: hearing the birds, the quiet of the day.

One day, around early 2014, during an awfully busy lunch rush, I came back inside after throwing away a bag, and I must have had a weird look about me because my coworker asked me what was wrong. I think I said something like: “What if every time I went out there, there was just a demon by the trash can throwing up?”

I kept having this sensation, even in other jobs, and eventually somehow it changed from a demon to an angel. I wrote this story in its entirety on Thanksgiving Day 2019, after carrying this vision all that time, and it finally clicked. Sometimes a story is like that, you carry it around for years, and when it finally clicks together, then the writing part happens fast.

Your story “The Eight Incarnations of Pascal’s Fifth” appeared in Huizache’s fifth issue in 2015. Can you tell us where you were in your writing career at that time? And what did it mean to you to have your story selected by Dagoberto Gilb for publication in Huizache?

My writing career was nonexistent when this story appeared in Huizache—any time a story is published still feels like a miracle, like your horse won against all odds, so luckily the feeling hasn’t diminished for me. Grateful that Dagoberto chose to publish it in this beautiful issue, it meant the world to me.

Learn more about Fernando’s books on his website: thewriterflores.com